A Man with a Mango

It was on a bus heading north from Trento in north Italy that I met you, the Man with the Mango. A train from just about the most south-western point of France, Port Vendres, to the just about most northern point of Italy, Trento. This is how it begun. Next was a bus that was to get me to an artist’s residency up in the hills half an hour north. My phone had no service, the sun had gone down, I wasn’t quite sure where I was going. I got off the train from Geneva and ran for the bus station. A young couple point me in the right direction. I don’t speak a word of Italian so trying to confirm with the bus driver that this was in fact the bus I was meant to be boarding was tricky, until you asked where I was going and told me through the warm smile that appeared on your face to get on. You threw my suitcase into the storage unit and we board the bus, sitting a few seats away from each other. I push my luck, lean into the aisle and ask if I can use your phone to message the friends I was headed for to let them know I was on my way. You offer your hotspot and I gratefully accept. You don’t speak much English, and either does your friend, but we chat a little as the bus curls around the road snaking up the mountain. You tell me you moved to Rome from Pakistan 10 years ago to cook, and when you grew tired of kitchens, you started working with your friend at a carpet factory. I tell you I’m there for the weekend to cook with friends who are feeding the artists at a performing arts centre for the summer. We talk about food for a little while — you tell me you miss the food of Pakistan, I tell you I miss the food of my parents. It’s then that your eyes light up and a smile appears. You swivel around in your chair and fossick about in the shopping bag on the seat next to you. After a few minutes, I wonder what the devil you’re up to. Then out comes a big, yellow mango balancing on the palm of your large hand. You explain to me what a mango is, and that it’s your favourite fruit, that it reminds you of home. Then you hand it to me like you’re handing over a crown. “For you,” you say. There’s something jolting and almost comic about seeing a mango so out of context, I wonder how far the closest mango tree is. I grew up eating mangoes as a child in Fiji and Papua New Guinea, sometimes climbing the trees and picking them myself, so I’m perhaps a little more familiar with this fruit than you realise, but I’m intrigued as to how one might speak of a mango if you’re speaking to someone you assume has never seen one. I ask you how to eat such a thing. You tell me to put a cross in the top and peel the skin down, almost like a banana, but your favourite way to eat it is in a drink: put it in the freezer when you get home, you tell me, then add some milk and blend it all together in the morning. I’ll always remember the joy in your face as you explain this, your favourite way to eat this tropical fruit.

We arrive at my stop, in the middle of what seems like nowhere, at the base of towering mountains, and you follow me off the bus to help me pull my bag out of the storage. The whole bus waits and watches as you ask if I’d like to get an ice cream over the weekend. As I write this, I look through my notes from July to find your name — there it is, sitting above a recipe for potato gnocchi, the dish my beautiful friend was making at 10 pm when I arrived at the residence that night. Sakunda. But to me, you’ll always be the Man with the Mango, the Kind Man with the Mango. The mango floats about the kitchen we’re cooking in over the following few days before we share it for breakfast one morning, not blended with milk, but cut the way I was taught by my father as a child — cheeks that get sliced into a grid then inverted so you can suck off yellow squares of flesh from the skin.

In case you’re wondering, the recipe for G’s potato gnocchi:

Boil 3 kg of peeled potatoes, mash the potatoes, mix in 300 g 00 flour and 10 g salt, followed by 3 egg yolks to form a dough. Roll the dough into snakes then chop inch-sized rounds off. Toss them in semolina and pop them in the freezer. When it’s gnocchi time, put a pot of boiling salted water on and once boiling, add the gnocchi — they’re ready when they float to the top. Toss them through your sauce, maybe something garlicky and tomatoey, and finish with a heavy shaving of parmesan and a heavy crack of fresh black pepper, and probably a drizzle of olive oil.

A Couple in Bordighera

It was dark outside as the train pulled into Bordighera, the second to last coastal Italian stop before you cross the border into France. I’d bought a train ticket to Sanremo but as we approached the seaside town, it felt too large, it didn’t feel like my place, so I stayed on the train. I type Bordighera into my phone — one of the towns ahead — and when I read that it is both the town the novel Call Me By Your Name is set and the town Jane Morris (William Morris’ wife) spent winters, I decided it was the spot for me that night. The carriage all stood as the train started to slow and we prepared to make our way down the cabin steps onto the platform. I start chatting to you and your wife. You tell me you’re from Boridghera and have spent your entire lives in the town. It makes me smile when you speak of how much you love it. It feels rare that you meet people who are so fond of where they live, where they’re from — perhaps that’s a generational thing. You’d been in Genoa for the day for a medical appointment, and for lunch. You ask about me, about my story. As we get off the train, I ask if you have any recommendations on a place to stay for the night. Without hesitation, you say, “Yes, I take you.” You grab my suitcase, walk your wife and I over to the car and open the passenger door. Your wife farewells me with a kiss on each cheek and you and I start the wander down the road, towards your friend’s hotel. After about about ten minutes of walking, as we pass a restaurant, you ask if I’ve had dinner. When I say no, you stick your head into the restaurant and greet them like family. You book a table for one in 20 minutes and we continue walking. You drag my heavy bag up the steps through the front door of the hotel, converse with the tired but kind-looking man behind the counter, and farewell me with a great big smile and wide open arms, all in a matter of minutes. I watch you scuttle off back down the dark street to your wife and I laugh as I stand in that stuffy-smelling lobby looking at the man dangling my room keys over the counter at me. I’ll never know your names, I’ll never see you again, but I’ll always remember you.

The Last White Asparagus

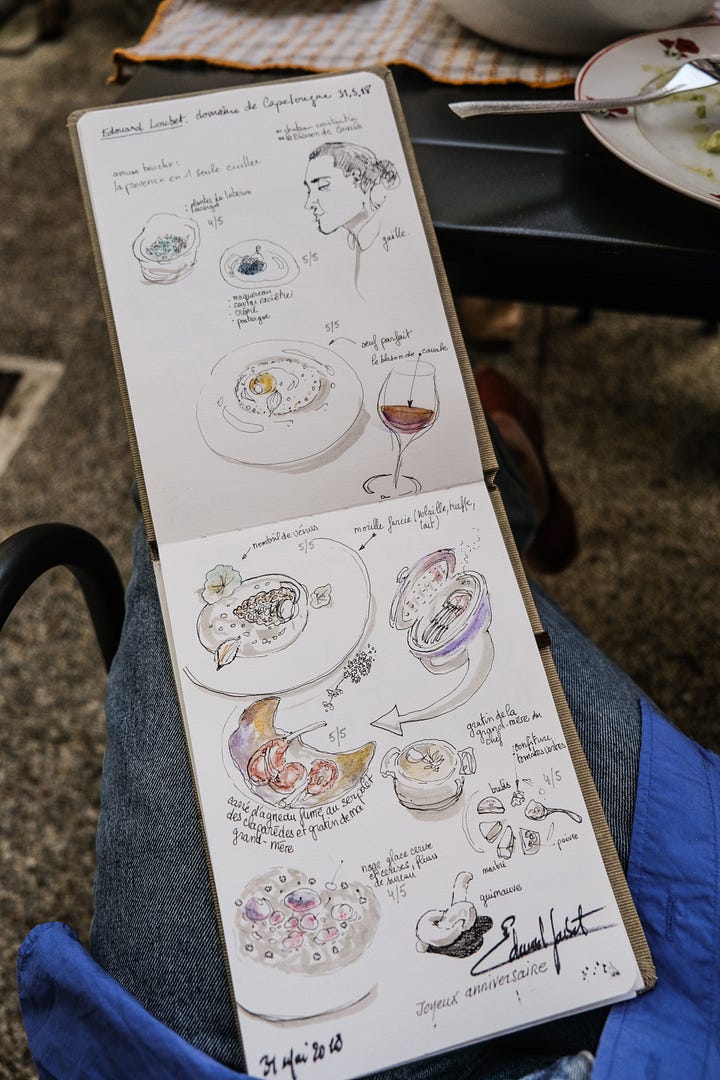

There were tears rolling down my cheeks as I wandered through your front door, into what I thought was just a gallery in this small town, Yèvre la Châtel, an hour and a half south of Paris. I felt I’d entered into a new world, like that scene in Narnia. I wipe the tears from my face and feel a smile appear as I say “bonjour” to you both sitting in what seems to be your kitchen and living room. I’d just said goodbye to my parents before they flew home across the world — the two people I find the hardest to say goodbye to, always. They’d dropped me off in this tiny village that looked like something out of a fairy tale, in the middle of nowhere on a dry summer’s day. You reply with a “bonjour” and softly start speaking to me in French. You’re warm and welcoming. You explain that Guillaume is an artist — a painter and illustrator — and you, Sandra, work in finance in Paris. You tell me you both commute back and forth, spending half your week in the country and half in the city. Your home sits in the heart of the village and you open it daily to exhibit Guillaume’s work, welcoming people into your living room while Guillaume sits and paints or draws. I tell you I’d just arrived to start a residency cooking at Aux Bons Vivres, the restaurant-association across the road. I’d arrived a few days early and there was not a human in sight. You ask if I have food for dinner and when I say no, without hesitation, you invite me for a meal, “It will be simple, the last of the white asparagus for the season, but you’re most welcome.” I arrive back a few hours later to your table, home to a plate of blanched white asparagus, a pot of boiled eggs, a bowl of cold and crisp radish, a plate of saucisson, some salted butter and a baguette. And a bottle of white wine from Sancerre. We sit and we talk, and Guillaume shows me his illustrations from scenes in restaurants from your recent vacation in Provence. You pluck a leaf from each of your new basil plants for me to try — one green, one purple. As I write this, I’m reminded of the perfection of this meal. The food, absolutely, but more so, the hospitality and warm welcome that this food enabled. A simple dinner, but one that changed me. I leave that night with your bike that you’ve leant me for the month, despite having only known me for a few hours. A most intense reminder of the power of sharing food, and the power of connection through food, especially when there’s very little shared language.

A Birthday Broach in Corsica

It was the day after my thirtieth birthday. I’d been laying on my bed reading Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book after a morning out on the boat free diving in the blue blue sea, before an afternoon and evening up in the cloudy mountains. I was bound for the bathroom when you walked through the door clutching something silver. I’d met you the night before when you popped by at midnight for a mirto — a liqueur made from myrtle that you’ll find filling glasses after dinner around the island. You’d told me that you are the neighbour, a Marseillaise woman who has lived in Propriano, in Corsica’s south, for 15 years after working in medicine around the world. I was in a daze from the morning sun and a lazy hour of reading as you wandered over to me and said to hold out my hand. You place a large silver broach in them and say with your thick French accent, “Bon anniversarie, lovely Harriet.” I felt to be dreaming. You explain that your friend had made it, and that you wanted me to have something special from l'Île de Beauté — the Island of Beauty — to remember my birthday, to remember the island with. “I’ll treasure it always, Françoise,” I manage in my dazed state. You turn around and leave and I stand there, clutching a handmade broach from a woman I’d spent no more than 15 minutes of my life with.

I wonder how you all are now. Where you all are now. Eating a mango somewhere in the mountains in the north of Italy, popping back to Genoa for a lover’s lunch, sketching a scene from your recent holiday as Sandra prepares a dinner of autumn’s vegetables, pouring a splash of mirto into a glass as you light your cigarette and sit under the stars of Corsica.

These moments of kindness are moments you carry with you forever. They’re all part of greater stories — a train journey along the Ligurian coast and French Riviera towards a life in Southwest France, a weekend cooking in Northern Italy with two women, two chefs, I’ve long admired, the beginning of a new chapter at Aux Bons Vivres, turning thirty in Corsica — but it’s in these small, seemingly simple moments that you really feel life in all its glory, that you feel what it means to be human, that you’re reminded of what makes this world feel beautiful, at least bearable, in moments when it’s burning in other places.

They’re moments that are baffling in the best kind of way, and are an intense reminder of the power of human connection, an intense reminder of the power of sharing food — whether it be a mango on a bus, a glass of after-dinner mirto, the season’s last white asparagus. It’s been a year that I’ve been living in a new part of the world, and I’ve been lucky to pocket up moments like this. They’ve given me solace and joy when I’ve needed it, and I wanted to write them down, both to share them, but also to distill them so that I forever remember the healing power of selfless kindness, particularly during times like this, when the world feels heavy from horrific human behaviour. We need every moment of kindness we can get, we can give — it’s infectious, and as I write, I am excited to pass on this selfless kindness to the complete strangers that I am yet to meet.

I’ve grown up listening to one of my wonderful father’s favourite songs, The Healing Power of Helpless Laughter by Tex, Don and Charlie. It inspired the title of this piece.

Reading your journal today is like a salve for my mind...soothing, full of warming and healing thought. Pure and open, devoid of selfishness and yet so very full of you and your openness to experience, love and humanity. Thank you Harriet (the spy, haha)

Balm.